Hands Across the Water

– The Case for a Combined Approach to Norwegian and UK Maritime surveillance Capability Challenges

After two decades during which the world’s security focus has been on the Middle East and beyond, the actions of a newly resurgent Russia, in Ukraine and elsewhere, are leading to a reappraisal of the European defence and security environment, and what this might mean for NATO and its member nations. Responding to this shift in the geo-strategic context is riddled with difficulty and complexity, as national governments struggle with the resourcing implications, while at the same time dealing with the impact of the 2007/8 economic crisis and the aftershocks that continue to unfold. And so inevitably there are gaps in the response – some of them critical to national security.

Among these is the ability – or lack of it – to locate and track ships and submarines in the north-eastern North Atlantic Ocean. It was not always thus. Not so long ago this was an example par excellence of how nations could work together towards a common aim, using a combination of political will, high-technology platforms, highly proficient crews and well-practised procedures to deliver an accurate, coherent picture whenever required. But with the demise of the Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) at Naval Air Station Keflavik, Iceland, following the US pivot to Asia, and the UK and Netherlands MPA fleets disbanded, only the Norwegian P-3 force remains in place, and then only with a limited time horizon as obsolescence bites. While surface and subsurface assets can clearly play a role, speed and altitude are required to deliver anything more than a tactical picture.

There is some hope, however, with the UK’s long-awaited decision to purchase nine P-8 Poseidon MPA and the emerging discussions about the reestablishment of USN MPA operations from Iceland. The P-8s will undoubtedly deliver an impressive spectrum of capabilities, but it is a very costly platform, which will inevitably restrict the numbers available, and so some important gaps will remain. The high cost also makes it questionable whether Norway will wish to opt for a P-8 purchase, especially given its parallel commitment to the F-35 programme.

The Hybrid MPA/UAS Concept

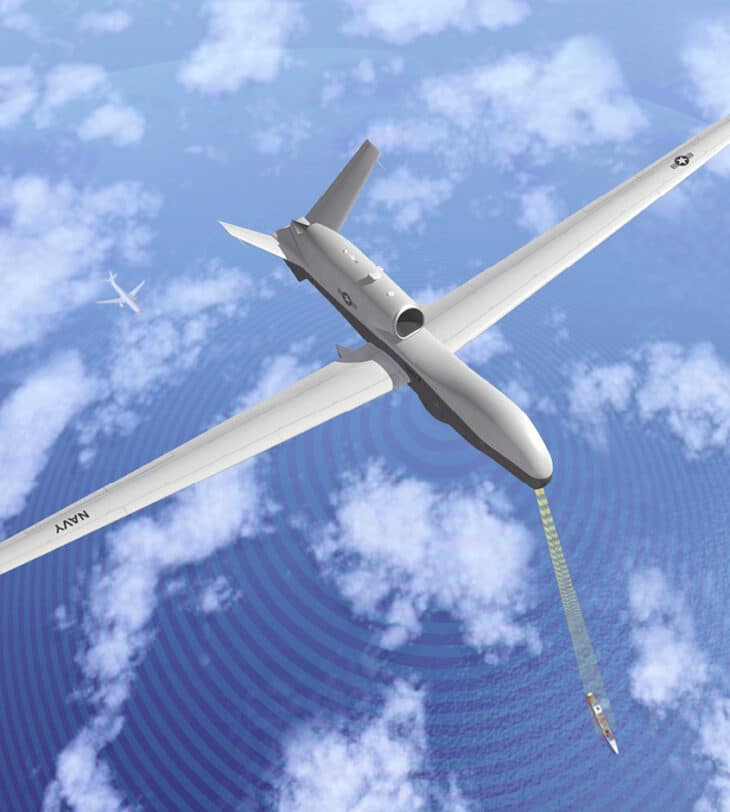

The USN (and indeed RAAF) are augmenting their P-8 forces with the MQ-4C Triton (using a force ratio of 5:3). This is far more than a cheap gap-filler, delivering a hugely impressive array of capabilities that will complement the P-8. Developed from the USAF’s RQ-4 Global Hawk (and retaining all of its overland ISR capability) the Triton has been upgraded for the maritime environment, and carries multiple payloads that offer 360-degree coverage to conduct a variety of missions. Operating for 24 hours at 50,000 ft, it is able to cover vast sea areas in a single sortie, and at roughly a third of the cost of a P-8.

Descent to low level for visual identification below cloud can be done efficiently when required, and the aircraft’s connectivity to its ground station and beyond allows rapid data transfer for exploitation and dissemination. If Triton holds the aces as far as surface surveillance is concerned, then it is the P-8 that does the equivalent when it comes to anti-submarine warfare (ASW). Equipped with a range of acoustic and non-acoustic sensors, it represents the current state of the art. Together, these two platforms are an immensely powerful and complementary pairing, able to deliver the necessary surface and subsurface picture in a far more cost effective manner than would otherwise be the case.

This cooperative proposition is further strengthened by the clear indication that the USN may return to Iceland, to Keflavik, to operate P8 ASW aircraft

The Potential for UK/Norwegian Collaboration

Budget constraints mean that a UK purchase of Triton for maritime surveillance is no more likely that a Norwegian P-8 buy. However, does the USN/RAAF mixed force concept offer a model that could be exploited by these two nations as a forcemultiplier? Could the two countries that sit astride the North Sea create and operate a combined force of nine P-8 and four high altitude, long endurance (HALE) unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), such as Triton, to deliver the required maritime picture more effectively and efficiently than on their own?

Several examples of defence capability delivered through burden sharing already exist within NATO, ranging from the UK-Netherland Landing Force to the Franco-German Brigade. And the political climate appears right between the two nations, with Norwegian Minister of Defence Ine Eriksen Søreide’s 2015 statement: “The UK is a key NATO ally and an important partner for Norway. Our close relationship as allies extends far back in time, and today we discussed opportunities for further cooperation.1” and the March 2012 signing of an agreement to strengthen inter alia bilateral military collaboration.

The UK would stand to gain much from such an arrangement. A single Triton sortie launched from, say, Andøya Air Base could provide a maritime surface picture stretching from Svalbard, west to Greenland, and down as far as the French Coast. While the P-8 is also an effective surface surveillance asset, it flies for typically a third of the duration and at three times the hourly cost, and so the efficiencies are obvious. With such a capable surface surveillance asset at its disposal, the UK P-8s could concentrate on the much more challenging role of ASW, along with search and rescue (SAR) and non-maritime tasks.

Norway would also benefit significantly from the arrangement. For example a Triton, the HALE UAS, is significantly more affordable than the P-8, and indeed the Orion it would replace, whilst at the same time delivering a step change in ISR capability to Norway. A single sortie could provide a surface picture of the entire Norwegian Sea, before going on to respond to the challenge of surface surveillance of the High North, an area of growing strategic interest to Norway as the shrinking ice cap increases accessibility to oil and gas, fishing and shipping routes. Alternatively, the extended duration and height at which it can loiter means it can sit close to areas of strategic interest for the best part of a day, searching deep into inaccessible territory for items of intelligence value. The replacement of the P-3 with the Triton would, however, mean a significant dent in Norway’s ASW capability. Other assets are, of course, available, but none have the speed, reach or flexibility offered by an MPA, and so the ability of Norway to draw on the UK MPA fleet for support would answer this question, giving the country access to a gold standard ASW platform at much reduced cost.

The success of the proposed arrangement would be underpinned by the shared agenda of both nations, driven by their geography and common foreign policy, defence and security interests. The whereabouts of a non-NATO submarine being tracked in the Norwegian Sea by an RAF P-8 is of just as much interest to Norway as the UK, as is the radar signature of a new non-NATO frigate, undergoing testing in its home waters.

Delivering a Combined Force

So how might such a combined force work? Cost pressures are likely to demand a light touch approach that has efficiency and effectiveness at its core. Existing C2 arrangements have for decades served the MPA forces of North West Europe well, often being tested during intense and protracted multi-national operations. But they also allow forces to operate independently on national eyes-only tasks where required, or indeed to operate as part of a NATO or coalition package, wherever necessary. Accordingly, there is little to argue for any form of combined Force HQ or even a new combined tasking organisation. The establishment of a Norwegian Forward Operating Location for RAF P-8s, logically at Andøya Air Base, could be done at little cost (indeed the Nimrod MR2 was a frequent visitor), and there might be scope for exchange postings between the two force elements, to further enhance the relationship.

Looking ahead, several enhancements also appear possible. While the HALE UAS is a long way from being able to match the P-8 as an ASW platform, work is underway to develop podded sonobuoy dispensers for these platforms. A UK company is working on micro-sonobuoys for deployment from these systems, as well as the necessary equipment to allow UAS to play a role within multi-statics and to relay acoustic data back to a ground station for exploitation. This could increase the utility of the HALE UAS segment to cover the search and any loose tracking phases of an ASW prosecution, before handing over to a P-8 if close tracking, or an attack, is required. Another enhancement could see the UK acquire its own HALE UAS, as a replacement for the Sentinel R1 in the overland ISR role. Such a development could result in the mooted Combined Force extending its mission set overland, and even offer the possibility of shared basing of UK and Norwegian HALE UAS in Norway, with the attendant benefits in cost and airspace complexities. This cooperative proposition is further strengthened by the clear indication that the USN may return to Iceland, to Keflavik, to operate P8 ASW aircraft. In this paper’s scenario, the Norwegian Tritons would maximize the capability of this larger and more viable North Atlantic USN and UK P8 aircraft force.

With such a capable surface surveillance asset at its disposal, the UK P-8s could concentrate on the much more challenging role of ASW

Conclusion

The Norwegian Sea is back on the front line and the maritime nations on its rim understand what this demands from a security perspective. However, budgets are stretched and every pound or Krone spent on defence must be made to count. With the UK having ordered the P-8 MPA, and Norway’s Orion fleet nearing the end of its life, these two nations have a unique opportunity to move ahead together, sharing the burden of airborne maritime surveillance by using a mixed hybrid fleet of MPA and HALE UAS, thereby delivering far greater capability at less cost, to the benefit of both, as well as to the NATO Alliance as a whole.

All that is needed is the political will of the two nations to make it a reality.