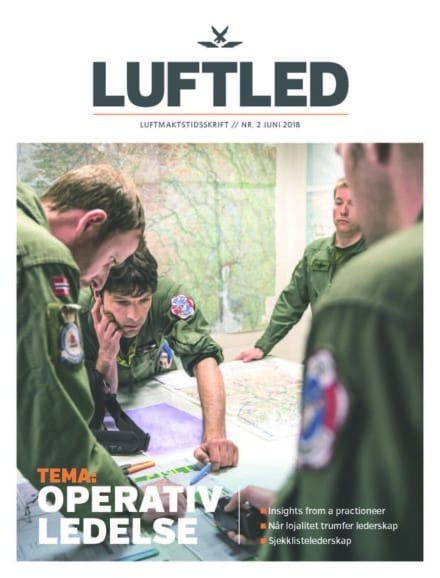

Operational Leadership: Insights from a practioneer

While the topic of leadership is of perennial importance, operational leadership is more relevant today than ever. Militaries that defend freedom around the world are faced with ever more challenging threats while at the same time resources allocated to defense are declining as a portion of government budgets.

The challenge is extraordinary—how to do more with less. Until societies support increased levels of resources for defense, military leaders can only look inward for better ways to use the means they have. One area of high leverage is how to best optimize human capital—the sine qua non of effective military operations. There is one sure pathway to lifting the effectiveness of a military organization—effective operational leadership.

There is no lack of material on the subject of leadership. It is extensively discussed in publications, presentations and courses in a wide variety of formats from academic to professional to experiential. All distill into a number of common leadership principles that translate to the art of operational leadership. However, there are also unique principles for exercising effective operational leadership.

Begins with competency

First, what is operation leadership? Most definitions of operational leadership focus on production of a desired outcome—or products. In the military the “products” are deterrence and the ability to fight and win wars. Generically, the “product” of military endeavors is mission accomplishment. Therefore, the desired outcome of operational leadership is the successful accomplishment of a task or set of tasks assigned by higher authorities.

All effective operational leadership begins with competency in a particular area of specialization or expertise—whether a pilot; radar operator; missile defense officer; engineer; communicator; or whatever else, competency is fundamental to good operational leadership. The reason is that competency breeds confidence in one’s ability to create desired outcomes. At early stages in one’s career those outcomes are the result of individual actions—for example, optimally piloting an aircraft through a series of maneuvers.

However, because of the character of military operations, all individual actions contribute to a much larger whole, or team. Air forces don’t succeed as single aircraft, but as formations of multiple, interdependent systems. They aggregate with other entities that ultimately form a force package, integrated defense network or organizations consisting of not just aircraft, but elements in the multiple domains of air, space, land, sea, subsea, and cyber. Teamwork is fundamental to operational success, and fundamental to leading teams is the ability to motivate people to act in ways they would otherwise not act without good operational leadership.

Empowerment

I believe that the single greatest element of good operational leadership is empowerment. Empowerment is a great motivator, because it carries with it the implicit bond of trust. Trust is foundational to a military chain of command unlike any other team. Trust in the military comes with the clear knowledge that decisions involving life and death may be made by those whom that trust is conferred upon. Great operational leaders provide their people with guidance with respect to the desired goals, objectives, end state, and then empower them to accomplish the details to achieve those outcomes. Empowered personnel are motivated to perform at their best because they understand the consequences of the trust bestowed upon them and that they are being relied upon to achieve a goal much greater than they alone could accomplish.

Good operational leaders do not tell their personal how to accomplish a mission, they first explain why an operation is being conducted—that provides context of understanding—and with that context, those empowered to act are motivated to optimize their competencies to achieve the desired outcome. This is the opposite of the disease of micromanagement and its associated disorder of risk aversion—or telling people how to do their jobs.

Unfortunately, today, as a result of modern telecommunications senior leaders often reach down to lower levels of command to direct specific actions as opposed to setting guidance and empowering those at tactical levels to execute.

Most definitions of operational leadership focus on production of a desired outcome—or products. In the military the “products” are deterrence and the ability to fight and win wars

Micromanagement

In Operation Allied Force, the Supreme Allied Commander Europe had a monitor on his desk so he could observe the streaming video from the MQ-1 Predator remotely piloted aircraft operating hundreds of miles away. One day he telephoned the operational level air commander and asked him what he was going to do about two tanks that were parked under a couple of trees. Such intervention is not the business of the Supreme Allied Commander Europe. More recently, in operations against the Islamic State, target engagements that could have been performed in minutes by airmen over the scene often took weeks—sometimes months—because of excessive concern over collateral damage by superiors far removed from the scene. On the opening night of Operation Enduring Freedom in October 2001, the opportunity to eliminate Mullah Omar and his senior Taliban leadership was squandered because the commander was more concerned about avoiding the risk of collateral damage to an unoccupied building than he was with the operational advantage that would have accrued by dispatching the Taliban leadership.

Risk avoidance can paralyze the kind of rapid, effective, decisive decision-making that is required for operational success. Unfortunately, in small scale contingencies and wars of choice, micromanagement and risk aversion are tolerated and often encouraged by political leadership because time and circumstances allow it. Not so in wars of consequence where time and decision cycles are compressed.

Example from Iraq

Let me illustrate with an example. By 1998, the no-fly zones in both northern and southern Iraq had been in place for seven years—since the end of the first Gulf War of 1991. Very specific procedures based on strict rules of engagement were established and a key element was that no weapons could be employed without the specific authorization of the respective combined/joint task force (CJTF) commander. On Dec 28th, 1998, the Operation Northern Watch (ONW) force package was back over northern Iraq enforcing the air exclusion zone after four days of not flying in the area as Operation Desert Strike was being conducted in Baghdad. Toward the middle of vulnerability window, an Iraqi SA-3 surface-to-air missile (SAM) site launched three Goa surface-to-air missiles at a flight of ONW F-16s (the SAMs were skillfully avoided by the F-16 flight). Dutifully, the airborne mission commander radioed back to the command center the request to employ force and it was immediately granted by the ONW commander. Within seven minutes the Iraqi SA-3 target tracking radar, and the associated three SAM launchers were smoking holes.

After that engagement, the ONW commander pondered why the established “consolidated operating standards” required the combined/joint task force commander to authorize the employment of force in situations where the international laws of armed conflict already allowed direct force employment in self-defense. The ONW commander made the decision to rewrite the “consolidated operating standards” to give the authority to employ force to the airborne mission commander while retaining for the ONW commander the authority to terminate the engagement if conditions warranted that call—they never did. That empowerment of the force on scene to make engagement decisions was liberating for the task force and for the mission. By the spring of 1999 the Iraqi air defense forces in northern Iraq no longer possessed any SAMs and were rendered ineffective.

The single greatest element of good operational leadership is empowerment. Empowerment is a great motivator, because it carries with it the implicit bond of trust. Trust is foundational to a military chain of command unlike any other team

The commander of the no-fly zone in southern Iraq—Operation Southern Watch(OSW)—called the ONW commander in the late spring of 1999 and asked him how he was able to accomplish that outcome. The ONW commander was a bit puzzled and answered that he had all the operational authorities to engage upon hostile intent by the enemy and built the operational conditions to do just that. The OSW commander commented that the command arrangements he was operating under required him to seek permission to engage not just from himself as the OSW CJTF commander, but also from his higher headquarters (Central Command Air Forces), and often additionally from that command’s higher headquarters (Central Command), and sometimes from that command’s higher headquarters (the Secretary of Defense). Some units with the same personnel often deployed to both ONW and OSW as a result of rotational tasking. The impact upon the unit personnel between the two very different leadership paradigms was dramatic.

Lead from the front

Effective operational leadership means understanding your authorities and exploiting them to the maximum benefit of the mission assigned. Leadership matters. It is easy to “go along to get along,” or not “rock the boat,” but the men and women in an organization will sense that kind of an approach in a very short period of time. That leadership style stifles innovation, mission accomplishment and spirit. Conversely, empowerment of the force to execute the mission that it is assigned creates the conditions that nurture the best in people and encourages them to contribute in ways that micromanagement and risk avoidance strangles.

At the same time, good operational leadership means enforcing standards; good order and discipline; and getting rid of non-performers. There is nothing that undermines the leadership climate in an organization more than retaining incompetent, underperforming, or disruptive individuals. Judgement is required. Here is where mentoring; teaching; and tolerance of mistakes is required. Making sure personnel understand that there is a difference between a crime and a mistake. Mistakes will be tolerated—crimes will not.

Great operational leadership also means providing an example that not only instills confidence in the organization but builds team morale. If you are given the opportunity to lead, then you need to lead from out front, not from the rear. The least experienced wingman sees that the senior most leader in the organization is willing to operate in the same threat environments that the wingman is exposed. This tenet applies just as much in the policy environment as it does in combat. Good operational leaders learn from their mistakes—bad leaders don’t acknowledge that they can make mistakes. Have the humility to recognize that as humans no one is perfect—including yourself.

Good operational leaders do not tell their personal how to accomplish a mission, they first explain why an operation is being conducted—that provides context of understanding

Competency, trust and empowerment

Generally, leadership is considered in the context of the leader exerting effort to garner action on the part of subordinates. However, I would offer that effective operational leadership is also a 360-degree endeavor. By that I mean that to be a great operational leader, you need to be able to positively influence subordinates; peers; and superiors alike. Influencing subordinates is the least difficult of the challenges operational leadership entails. Here are two short bits of counsel in dealing with peers and superiors: one; convince your peers and/or superiors that your ideas are actually his or her own ideas, and two; don’t worry about who gets the credit—those two rules will get you, and your organization a long way towards mission success.

There are many other traits that contribute to operational leadership success—courage; listening well to all who can contribute; passion for accomplishment; empathy; awareness; healing; persuasion; foresight; stewardship; and others, but ultimately the fundamentals rest on competency, trust, and empowerment. In the United States Air Force our core values are expressed in terms of: integrity first (trust); excellence in all we do (competency); and service before self (contributing to being part of something much bigger than oneself). Great operational leadership is a contact sport. Seek every opportunity to exercise it.

Good hunting.